News Hub

Home » Highlights

21 February 2026

NUS School of Computing took part in its first-ever reciprocal computing exchange programme with the School of Informatics at Nagoya University. From 8 to 16 December, 14 NUS Computing students joined their counterparts in Nagoya for an academic and cultural immersion focused on artificial intelligence, robotics, and system design.

14 February 2026

12 students from the NUS School of Computing (SoC) proudly represented Singapore at the SEA Games 2025 in Bangkok, Thailand – demonstrating exceptional dedication as they balanced national-level competition with their academic commitments at SoC, supported by faculty and peers along the way.

11 February 2026

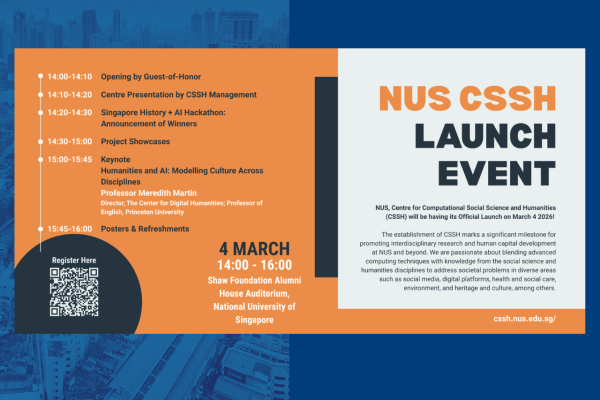

The School of Computing is pleased to support the launch of NUS' NUS' Centre for Computational Social Science and Humanities (CSSH) — a centre that brings computational approaches into closer dialogue with the social sciences and humanities.

9 February 2026

The AI programme at the NUS School of Computing has been named among the world's leading universities for Artificial Intelligence in the 2026 Analytics Insight rankings.

4 February 2026

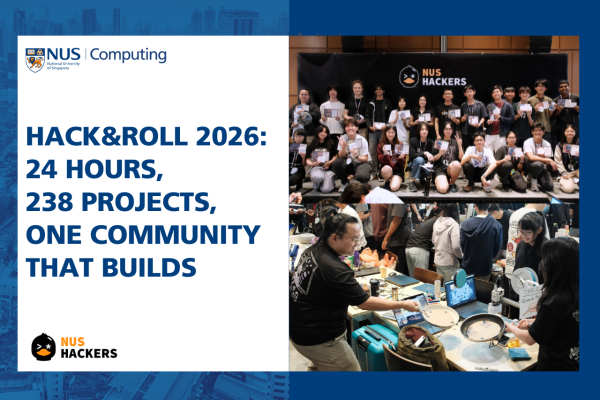

When 800 participants gather with laptops, soldering irons and a single question: what can we build? The answer is never just one thing.

Hack&Roll 2026, the flagship annual hackathon organised by NUS Hackers, returned this January for its 15th edition, bringing together builders from across Singapore’s tech community for 24 hours of open-ended experimentation, creativity and problem-solving.

2 February 2026

NUS School of Computing took part in its first-ever reciprocal computing exchange programme with the School of Informatics at Nagoya University. From 8 to 16 December, 14 NUS Computing students joined their counterparts in Nagoya for an academic and cultural immersion focused on artificial intelligence, robotics, and system design.