The High Stakes of Enterprise System Adoption

Implementing a new enterprise system is one of the most ambitious and risky moves an organization can make. Whether it’s a customer relationship management (CRM) platform or a massive enterprise resource planning (ERP) overhaul, the promise is transformative: streamlined operations, smarter decision-making, and increased competitiveness.

But the history of enterprise system rollouts is littered with cautionary tales. Hewlett-Packard’s $160 million misstep and RichCon Steel’s bankruptcy are just two dramatic examples of what happens when good intentions meet harsh reality. Despite best efforts and massive investments, many systems fail not because of poor technology but because of people – the users who are expected to integrate these complex tools into their daily work.

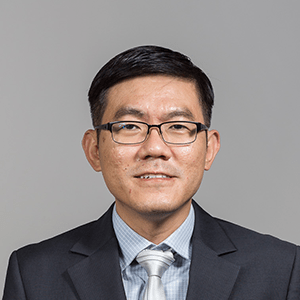

Understanding not just whether employees use new systems, but how they use them, routinely or innovatively, turns out to be critical. This deeper layer of insight is the focus of a groundbreaking new study by NUS Computing’s Associate Professor Tan Chuan Hoo, and his collaborators Prof. Ke Weiling (NUS IS PhD Class of 2004 and Professor and Chair at Southern University of Science and Technology, China) and Prof. Wei Shaobo (Professor at Hefei University of Technology, China). It offers a nuanced look at how leadership style, support mechanisms, individual mindsets, and system design interact to shape outcomes, and why strategic management of these factors is essential for success.

Routine vs. Innovative Use: The Hidden Dynamics of System Adoption

At the heart of the study lies a key distinction between two types of system use: routine use and innovative use. Routine use refers to employing the system in expected, standardized ways, following processes as designed. It’s about efficiency, predictability, and minimizing errors. Innovative use, on the other hand, involves employees experimenting, adapting, and finding new, perhaps unanticipated, ways to leverage the system’s capabilities to enhance performance.

Both are vital. Routine use ensures the system’s core functionalities are realized; innovative use unlocks the system’s full transformative potential. Critically, the study shows that different organizational practices encourage these different types of uses, with significant implications for both job performance and employee satisfaction.

What Drives Routine and Innovative Use?

The study identifies two major drivers: leadership style and the type of support structures offered during system implementation.

Transactional leadership, characterized by clear instructions, monitoring, and rewards or punishments tied to compliance, nudges employees towards a prevention-focused mindset. This mindset emphasizes caution, error avoidance, and meeting minimum expectations. Not surprisingly, prevention-focused employees tend to use systems in routine, safe, predictable ways.

Transformational leadership, in contrast, fosters a promotion-focused mindset by inspiring employees with a vision of growth and encouraging creativity and self-efficacy. Employees in this mode are more willing to explore and innovate, discovering novel ways to use the system that weren’t part of the initial playbook.

Similarly, impersonal support mechanisms, such as standardized user manuals, help guides, FAQs, align with prevention-focused behaviors, helping employees avoid mistakes through clear, uniform guidance. Conversely, personalized support, through help desks, peer support networks, and super-user champions, boosts confidence to innovate by providing tailored assistance when employees venture beyond routine usage.

In other words, organizations have levers to subtly but powerfully influence whether employees stick to the script or write new ones.

The Role of System Design: Why Modularity and Complexity Matter

Technology itself is not neutral in this process. The study highlights two key system design features: modularity and complexity.

Highly modular systems, built from distinct, interchangeable components, strengthen the relationship between prevention-focused employees and routine use. Modularity lowers perceived risk by allowing users to compartmentalize their interactions with the system. If one module is learned and mastered, it doesn’t threaten the entire workflow.

However, modularity surprisingly does little to promote innovative use. This may be because modular structures can unintentionally create silos, limiting the kind of cross-functional exploration that fuels breakthrough ideas.

System complexity has an even more intriguing dual effect. For prevention-focused users, high complexity weakens routine use because it increases the perceived risk of errors. For promotion-focused users, however, complexity acts as a catalyst, offering a rich environment for exploration and creative problem-solving.

In short, the system’s very architecture can encourage or discourage different user behaviors, depending on employees’ mindsets.

Impact on Performance and Satisfaction

Both routine and innovative uses have positive effects on supervisor-rated job performance. Employees who use the system efficiently and reliably are valued, as are those who find ways to extract even greater value from it.

However, when it comes to employee job satisfaction, only innovative use makes a clear difference. Employees who feel empowered to experiment, adapt, and improve how they use the system report greater job satisfaction. Routine users may perform well, but the sense of engagement and fulfillment that fuels long-term retention and morale comes largely from innovation.

This finding is crucial for organizations worried not just about immediate performance metrics but about fostering a vibrant, resilient workforce.

Strategic and Managerial Implications: What Organizations Must Do

The implications of these findings are profound for any organization investing in enterprise systems.

First, change management strategies must go beyond technical training. It’s not enough to ensure employees know which buttons to click. Managers must actively shape employee mindsets, using leadership styles and support structures that align with desired behaviors. For example, if the organization’s primary goal is to standardize processes and minimize errors in a highly regulated environment (like finance or healthcare), a transactional leadership style, strong impersonal support, and a modular system design may be most effective. However, if the aim is to unlock new capabilities, foster innovation, or adapt to rapidly changing market conditions (as in tech startups or creative industries), transformational leadership and personalized support become critical. Complexity, if well-managed, can actually be an asset rather than a liability.

Second, executive sponsors and project leaders must tailor communication strategies. Routine-focused users need reassurance about expectations, error avoidance, and compliance support. Innovation-focused users should hear messages about empowerment, exploration, and growth.

Third, system design decisions must be made with user diversity in mind. Different users will interact with the same system very differently based on their regulatory focus. Offering flexible pathways – where modularity is balanced with opportunities for cross-functional integration – can cater to a wider range of users.

Fourth, organizations must monitor not just usage metrics but usage styles. Tracking login counts or process completions is not enough. Companies need tools and assessments to understand whether users are sticking to routine or innovating, and adjust their support and leadership practices accordingly.

Finally, reward systems must recognize both routine efficiency and innovative breakthroughs. If only compliance is rewarded, innovation will wither. If only risk-taking is praised, stability could suffer. Smart organizations will build dual recognition paths into performance evaluations.

Future Enterprise System Use: Unlocking New Possibilities

Looking forward, the insights from this research open exciting possibilities for the future of enterprise technology deployment.

In the era of AI-assisted systems, for example, companies will need employees who not only use AI tools correctly but who also imagine new ways to integrate AI into workflows. Routine AI usage will automate efficiency; innovative AI usage will differentiate leaders from laggards.

In remote and hybrid work environments, empowering employees to creatively adapt enterprise collaboration tools could be a key competitive advantage. Teams that find novel ways to use virtual workspaces, project management platforms, and digital communication tools will be more cohesive, productive, and satisfied.

For industries undergoing digital transformation, like manufacturing moving into Industry 4.0, nurturing innovative system use could accelerate the adoption of smart factories, IoT integration, and real-time data-driven decision making.

Even in public sector organizations, where risk aversion is often high, selectively encouraging innovative use of citizen service platforms could unlock better engagement, efficiency, and public trust.

Conclusion: Mastering the Human-Technology Partnership

Ultimately, the success of an enterprise system is not just a matter of software quality or installation efficiency. It’s a human story; a story about how people engage with technology, either as cautious followers or as creative trailblazers.

This study reminds us that companies don’t have to leave that engagement to chance. Leadership style, support structures, and thoughtful system design can all nudge employees towards more effective, satisfying interactions with technology.

By embracing these insights, organizations can finally unlock the true potential of their enterprise systems, achieving not just operational excellence but strategic advantage in a digital world that rewards both efficiency and innovation.

Further Readings: Wei, S., Ke, W., Tan, C.-H. (2025) “Routine and Innovative Use of Enterprise System: Intricacy of Change Management Levers, System Characteristics, and Regulatory Focus,” Information Systems Research DOI: https://doi.org/10.1287/isre.2022.0160